Thanks to a chance introduction to Anne Richardson of the Oregon Cartoon Institute during the Western History Association conference this past Thursday, I learned about a fun 1974 film by Homer Groening (yes, Matt’s dad), The New Willamette. I’ve viewed the ~26-minute film a couple of times today, and, in the spirit of my analyses of other Willamette River films (such as here and here), below the jump are some of my initial thoughts . . .

A post at the 16mm Lost & Found blog provides a link to where one can view this film on the Indiana University Media Collections Online site. The blog post also provides a bit of context on the film and on Groening.

From a film narrative perspective, Groening’s film starts in Portland and heads upstream, which is the opposite of William Joy Smith’s 1940 silent film, Willamette River Pollution. Seems fitting: Smith was constructing a visual narrative of how the river started pure in its headwaters and became increasingly more polluted downstream until it was absolutely vile in Portland Harbor, whereas Groening begins by showing how successful the cleanup had been by 1974 in its worst stretch–Portland to Oregon City–and then heads upstream to showcase happy fishers, recreationists, and fish hatchery staff.

It struck me toward the end of Groening’s film that neither McCall’s Pollution in Paradise nor Groening use any footage from–nor make any mention of–Smith’s 1940 film. Groening even has a segment explicitly about the “old times” (starts about 10:35) and he includes some old-timey footage of steamboat traffic, but he doesn’t use any of Smith’s footage. My initial interpretation of this is that Smith’s film was lost not only physically (i.e., unavailable in libraries or archives), but also lost to memory. That’s unfortunate, as it played such a critical role in abatement advocates’ struggles against City of Portland officials between late 1940 and early 1944 to pressure the city into developing a meaningful funding mechanism to build Portland’s sewage treatment infrastructure (see, for example, my earlier post “Willamette River pollution film, 1940“).

Groening interviewed McCall for his film, which would have been an absolute requirement. However, he doesn’t speak with any Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) staff, whereas in Pollution in Paradise McCall centered much attention on the DEQ’s predecessor agency, the Oregon State Sanitary Authority; McCall even filmed Authority members “in action” and interviewed chair Harold Wendel.

Groening also, like those who conducted the oral history of long-time abatement advocates David B. Charlton and Ken Spies, doesn’t seem to know enough about the background of the clean streams fight from the 1920s through the 1960s to formulate anything but surface-level questions. This is likely a reason why, when he establishes that one purpose of his film is to showcase the Willamette as example of steps to make a river cleaner (starts at 23:21), he never specifies what those steps were. He relies on his narrators to describe these steps in an extremely over-generalized manner. For example, McCall (23:40-25:24):

“In the days of the Indians we had the kind of river with the water you see in it today. But in-between the time of the Indians and today, we punished this river. We watched giant floods tear trees and soil from its banks and even inundate villages and houses. We polluted this river shamefully. We almost killed–well, we did kill–its anadromous fish life off. I think we did it knowingly, but not in the sense that we’re going to kill a river, but we didn’t know how easy it was, cumulatively, by people and industry to turn one of the great rivers into an open sewer. And then we started forty years ago saying ‘what are we gonna do?’ And so as a citizen group merged into a state group called the Sanitary Authority, we started doing these things. We started honoring what is the largest river, self-contained in any state. We returned the river to its condition three years ago, and there is a great system of dams now by the Army engineers, that prevent those floods. There are runs of salmon starting now that promise to be even more tremendous than they ever were in historic times. And people swim in this river now, where there used to be ‘no swimming’ signs in many parts of it. People boat in it, they fish in it, and it has become again a thing of joy, a thing of pride, an old friend. A river with a personality to everyone who lives along it.”

Finally, in this film neither Groening, McCall, nor Jim Conway draw any connections about how important the Willamette Valley Project dams were for improving water quality. They refer to the dams, rightly, as critical for flood prevention, but they provide no insights on the critical role these dams also played (and continue to play) in helping maintain water quality (see, for example, this post).

Here’s a good quote from Groening (21:29-21:34): “The story of the new Willamette is not where the water gets its start but in what we’re doing to it on its way to the sea . . .”

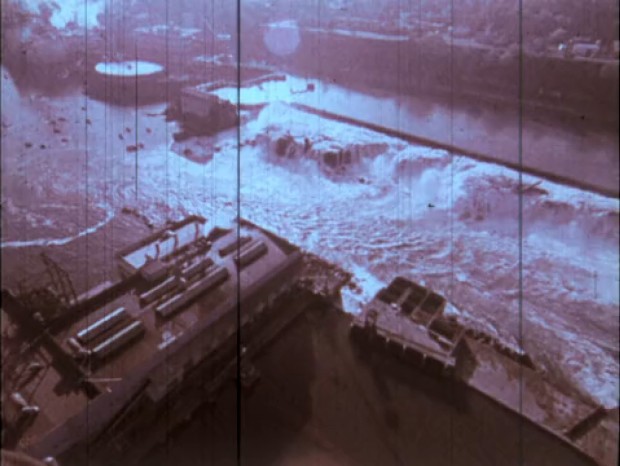

Some good stills from the film: